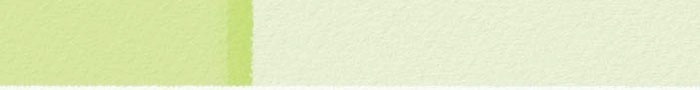

Lou Harrison (1917-2003) used to live just north of the UC Santa Cruz campus, in Aptos, and had any number of contacts with the music department there—in fact, for those of you who know Santa Cruz, it was partly Harrison’s interest in non-Western music, especially Gamelan, that led to Javanese Gamelan music being a major option for UCSC undergraduates (not exactly the most common choice). That influence appears totally absent in this piece, however, a free-floating air without a precisely defined melody or time signature. It seemed so well-suited to the steel-stringed guitar that I performed it twice, once on the classical, and then on the Taylor.

Harrison loved just intonation, an alternative way of tuning instruments that is no longer widely used. For reasons too complicated to explain here, when you tune an instrument, you have two basic choices: it can either be perfectly in tune in one key (say G major), and noticeably out of tune in the others, or it can be a tiny bit out of tune in every key—not really noticeably, though. The “tiny bit out of tune” is generally how we tune our instruments, and is called “equal temperament.” Harrison wanted to experiment, though, and has works for microtonal instruments (microtonality refers to splitting the octave into more than eight notes, or 12 diatonic notes—that is, there might be a note in between D and D#!), and a lot of work for just intonation. That’s the case with “Serenade for Frank Wigglesworth,” which should be played on a justly intonated guitar. (They make some, with movable frets, but I don’t own one).

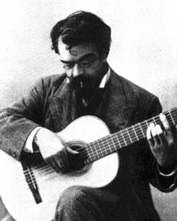

As you can see from the picture, Harrison was just what you’d expect from a long-haired, hippy, gay, peace-activist, Esperanto-speaking (the original title of this piece was “Serenado por gitaro”) composer who lived in the hills of Santa Cruz—he’s also a great composer, dedicated to seeking out the new, but equally insistent that music be beautiful. I heard the “Serenade” on the radio after dropping my son off for school, came home, found the sheet music online and learned it by that afternoon; I’m working on some other pieces by him, as well, but they’re harder. And for the record, “Frank Wigglesworth” was a real person, a friend of Harrison’s. I assumed it was just a made up name when I first heard the title (and the piece is sometimes just called “Serenade”).

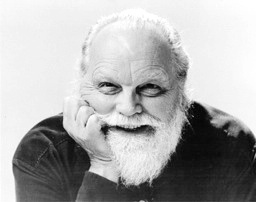

This is a piece by Manuel Ponce (1882-1948) which has been in my repertoire forever, since Santa Cruz, but which I forget and then periodically re-discover. It’s a rather slow piece, and somewhat brooding, divided into a number of repetitions of the same theme (especially noticeable when it gets replayed on the bass strings). It also seems to be based on an opposition between the softly strummed portions and sudden, marked, punctuated chords.

Ponce was a Mexican composer, and his works reflect the 19th-century preoccupation with folk melodies and “national spirit.” Many of them are elaborations of popular melodies, a technique frequent in guitar music, since the instrument itself is so closely tied to popular music.

There are at least twenty-four of these preludes, and there are recordings of all of them.

“Sakura” is a traditional Japanese piece. The structure is straightforward—an introduction and a conclusion frame the piece, which is a theme and then a series of variations. Some versions have several more variations (I just used the music that I could find on-line, which is a theme and four variations), and the variations are mostly technical. That is, the first variation restates the theme using arpeggios; the second using artificial harmonics; the last using tremolo.

Despite being traditional Japanese music, it lends itself remarkably well to being played on the guitar, both technically as well as melodically and harmonically. For me, the overall effect is fascinating: most of the piece simply sounds strange, a bit otherworldly, without having a stereotypically “Eastern” sound (this may be the strictly pentatonic scale at work). This piece completely grabbed me—again, I heard it on the radio and immediately got the sheet music and started learning. For a piece with a lot of fast playing, I must say that it was extremely “learnable” and came together very quickly. The tremolo still needs work, but, add in some reverb, and who can really tell?

“Sakura” means, of course, “cherry blossom” in Japanese. It is also the longest single piece that I know, weighing in at over six minutes, and if I can find a version with more variations, it can get up to nine minutes in length.

Francisco Tarrega (more formally known as Francisco de Asís Tárrega y Eixea, 1852-1909) is sometimes called the “father of the modern classical guitar.” Perhaps that’s a bit of an exaggeration, since manuals on method and repertoire exist well before him (such as Carcassi), but he helped turn it into a recital instrument; it was no longer to be used exclusively for accompanying other instruments. He did so the same way that Segovia would several decades later: a combination of virtuoso playing and transcriptions of already famous works composed for other instruments. Tarrega also composed some of the pieces best known for the guitar today, including a really famous, knock-out piece, entitled “Recuerdos de la Alhambra.” Amusingly, however, that’s not actually his best known piece: Tarrega is responsible for the most widely used cellphone ringtone, the default ringtone for most Nokia phones. Obviously he didn’t intend for it to be used as a ringtone: it’s from his “Gran Vals,” instead.

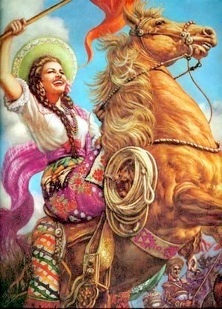

“Adelita,” however, is most often associated with another tune by the same name, commemorating the Mexican revolution. Adelita is a classic “woman warrior” figure, and is a significant part of Mexico’s revolutionary iconography. It is not at all clear to me, however, that Tarrega’s “Adelita” is this same figure. It is also quite possibly the shortest piece I know, and has one of the hardest B sections to play correctly at tempo. But thanks to modern recording technology I was able to use a take that was fairly close to correct.

Another piece by Francisco Tarrega, and this one is extremely well-known. It is a typically classical composition, rigorously logical in its development and written in a standard ABA structure—it is, however, infused with a more typically romantic sweetness and longing (“lagrima” is Spanish for “tear”), and the minor key B section heads into passion more typical of romantic music.

“Lagrima” is the first piece of real classical guitar recital music that I learned—I had learned some basic studies before, but this was recognizably music to me. I also once played it as an impromptu duet with my brother, who was—as usual—on the kazoo.

I heard this piece on the radio one morning coming back from school, and this was the moment that I discovered that the world of classical guitar had changed. Radically.

I remembered that the piece was by Torroba, since he’s one of my favorite composers for classical guitar (I recorded eight of his pieces when I was in graduate school ten years ago), as well as the title “Sonatina.” On a whim, I typed in “Torroba Sonatina” into Google, and did an image search. Sure enough, after some looking, I found the sheet music in high resolution .pdf and .gif files. Along with reams of other classical guitar music. “Nice!” I thought. And five minutes later, I was starting to learn the piece. A couple of moments called for difficult stretches, however, or had unclear fingering. But a few more minutes, and I was watching a YouTube video of the piece being played by an expert—and the video was clearly filmed by a guitarist. There’s barely any shot of the performer’s face—just his hands, and mostly the left hand. I learned the second movement of the “Sonatina” in an afternoon, probably the fastest I’ve ever learned a piece of similar complexity and length. I can’t imagine going back to the old way—to be able to get sheet music instantly, high quality recordings, and instructional videos, all for cheap or free, is pretty astonishing.

This one is a favorite of beginning guitarists everywhere—it’s simple to play, easy to read, and it sounds amazing. It’s also managed to escape the trite, conventional character of some of the more popular pieces. And that’s no surprise, since it’s actually composed by Erik Satie (1866-1925), a radical, avant-garde composer who knew Debussy, Ravel, Coctaeu, Picasso and the like. When he wasn’t organizing socialist collectives, he was composing dadaist music or working with Picasso on theatrical productions.

Like much avant-garde music, Satie’s works were often humorous, frustrating or baffling. The “Gymnopédies,” are none of these things, however. They are atmospheric in character, almost trance-like at times. Satie himself called some of his music “furniture music”—music to be played in the background. Are the gymnopédies elevator music? Elevator music elevated to an art form?

Another piece by Torroba, and often closely associated with Segovia, as are many pieces by Torroba. This “Castilian Suite” is meant to bring out multiple elements of Spanish folk music, and the elements of flamenco and Spanish popular music are evident here. The “Fandanguillo” and especially the “Danza” are quite difficult in some passages, especially the need to rapidly alternate different timbres. The “Arada,” on the other hand, is not technically challenging, but is a beautiful piece nonetheless. Unfortunately, I recorded the Arada and the Danza weeks after recording the first movement, and I’m not a great audio engineer—they have very different acoustic qualities, to my ear.

If you check out YouTube, you can find a lovely video of Ana Vidovic (and she herself is quite lovely) playing the “Danza” at a really impressive speed. So impressive, in fact, that it raises the question: how fast is too fast? Her rendition (terrible audio quality) I think may actually just be too fast, too fast for the listener to actually appreciate what’s going on. The normal answer of a guitarist to “how fast is too fast?” is “there is no such thing as too fast.”

A gorgeous piece in dropped D tuning that makes extensive use of artificial harmonics. Harmonics are those chime-like tones that guitarists play, typically by “hovering” a finger just above a particular fret (the 5th, 7th and 12th work well), but not actually pressing the string down, and playing the string while immediately releasing the left hand. This gives a limited number of “special” notes, with a characteristic chime or harp-like sound.

You can actually do this to any note on the guitar, and if you’re really clever, you can do it while playing other, normal (i.e., non-harmonic) notes. That’s what happens here. The first time I saw it I thought a god had descended to play the instrument and that I would never be able to play it. It took a few weeks, but like a lot of showy techniques (Van Halen hammer-ons?) it’s surprisingly doable once you get used to it.

The cello suites are some of Bach’s most loved pieces (and performed by any cellist of major caliber). The first suite is probably the best known, and the “Prelude” appears prominently in the cult lesbian vampire film The Hunger (1983), which is—somewhat sadly—how many people of my generation got to know it. This piece is distinguished both by its inventive, almost minimalist opening on just a few barely sketched-out arpeggiated chords and by its breathtaking ascending end, as thirds chromatically go up the neck of the guitar. The middle’s nice, too.

I can’t say I do any of these pieces justice. I’ve played them for years—since 1987, in fact, when I learned the second Menuett—but Baroque music really requires its own specialization. I still love them, though, and decided to record them so I’d at least have a record of playing them.

* * * * *

The Allemande is the longest of the six (seven, if you count the Menuetts separately) movements in this first cello suite, and its difficulty is its simplicity: it offers you nothing more than a long, wandering melodic line, full of tension and release. It’s hard to know how to interpret such a piece, given its lack of structure. In part, this is what you have to emphasize, so that it stands out, especially in comparison to what follows.

* * * * *

Quite unlike the Allemande, the Courante is a merry, fast dance, filled with melodic sequences (where Bach will repeat and alter a basic component of the melody—playing a rapid scale, and repeating it higher and higher). It is possibly the most difficult of the movements to play, not so much because of its speed (the Gigue is faster), but because it keeps a complex melody in the bass even in its fastest moments. Typically for Bach, the B section is substantially harder to play, and especially irritating is that the last three measures (the third to last in particular) are nearly impossible to play. I’ve taken liberties, cleaned things up a lot with various bits of digital technology, and even cheated in one spot—I’ll let you guess where!

* * * * *

The Sarabande, in nice contrast to the Courante, is probably the easiest of the cello suite to play—it is generally the slowest, as well as the one that offers the greatest degree of interpretive freedom.

A sarabande is a dance in a triple meter with a fairly distinctive rhythm. It has the honor of having emerged from central America early in the colonial period (in the 1500s), whether from Spaniards innovating on pre-existing forms, or from an interaction between European music and indigenous music is not quite clear. In any case, it moved first to Spain and then to the rest of Europe in a much slower form—eventually, it became a standard part of the Baroque suite, which is how you see it here. How interesting, however, that the discovery of the Americas by Europeans, which happens at the end of the 1400s, has been invisibly integrated into the heart of the most elite forms of European art music in less than 100 years. So much so, in fact, that no one even realizes it.

The first two chords, by the way, are identical to those that begin Rush’s “Fly by Night” and the old (c. 1970s) Channel 8 News theme song from San Diego. If I ever get a 12-string guitar (not very likely!), I’ll immediately record that theme song, which is a great piece of music.

* * * * *

Bach was quite a stern fellow, as this—and every other image of him—shows. The story is that his children had to harmonize a chorale without errors before they were allowed to have breakfast. And he had twenty children (13 with his second wife, if you can imagine), but since it was the early 1700s, only half of them survived childhood.

* * * * *

The happiest and fastest of the various parts of the suite, the Gigue is also the most dance-like in its character. All the movements of all the suites (Preludes excepted, of course) are named for dances: Courantes, Bourrées, and so on. It is unlikely anyone actually danced to these, but their rhythms and character often emerged from a particular kind of popular dance.

The Gigue also features some notably difficult passages, both for their complexity and their speed. They occur in the B section (as they almost always do)—I recorded this movement slightly differently, more “naturalistically,” with little preparation and leaving in more of the mistakes. That seemed in keeping with its almost impromptu, spontaneous character.

Antonio Lauro wrote this piece, a staple of guitarists everywhere. It’s an impressive piece, and it doesn’t take a ton of work to get it up to speed. Happily, it can also be played with a great deal of expression.

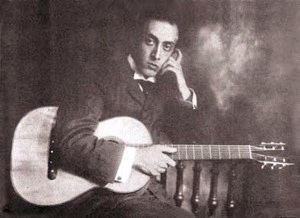

Lauro was a Venezuelan composer, and like most modern South American composers for the guitar, drew fairly heavily on local and popular themes and techniques for his music. This piece was actually written in prison, where Lauro had been placed by the military junta for a belief in democracy—a risk everywhere, but especially in South America. Especially if you’re as dangerous and radical looking as this gentleman.

The story goes that this piece was composed by the well-known French composer Francis Poulenc in memoriam the guitarist Ida Presti. Presti was a virtuoso guitarist from the 1930s through the 1960s, especially known for her duet performances with her husband, Alexandre Lagoya. You can catch some YouTube videos of her performances, and even with the execrable video and sound quality, it’s pretty clear that she was astonishingly good. She died quite suddenly and unexpectedly in 1967.

The funereal qualities of the piece are evident, from its slow, stately rhythm to its mournful harmonic character. The ending is particularly marked by a sudden and heavily marked resolution to A—the moment of death—and then each of the strings is played and held, open, ascending, more and more slowly:

E A D G B E.

And so the strings mark out the ascent of the soul, but also the soul leaving the guitar behind, each string played one last time. So the piece is a farewell to Presti, and a farewell to the guitar.

Or so it was explained to me, and I’ve read similar interpretations since on the internet. Unfortunately, the piece was written in 1960, seven years before Presti died. But it makes a great story!

Whenever I pick up a steel-string guitar in DADGAD (an alternate tuning that guitarists sometimes use, especially in folk music and Irish music), something comes out. And when I bought my Taylor shortly before my son was born, this is what came out. I call it an improvisation since although I know the parts and the general order it never comes out the same way twice. Listen for the harmonics!