The context for this post comes from a previous post thinking about gender as a strategy, specifically a Darwinian or evolutionary strategy, and what that might mean.

Evolutionary psychology proposes that humans evolved certain fears, desires, habits and cognitive structures over millions of years (evolutionary time). We evolved those features for the same reason other animals evolved their features: they helped us survive and flourish; as a result, those features became more common, even dominant, over time. Animals with natural camouflage are a nice example—when camouflage is really successful, like a tiger’s stripes or a leopard’s spots, it can become so dominant and widespread that every member of a species has it. It’s no longer variation within a species—it is the species. With really good adaptations, such as those that help an animal survive longer or attract a mate, we should expect to see them become totally dominant in this way.

But not every trait becomes so dominant, even when it is useful. Sometimes, traits are more like a strategy, a potential path to victory. But in the real, competitive, and constantly changing world of Darwinian competition, there are probably many paths to evolutionary success.

For example, all other things being equal, it’s probably better to be bigger rather than smaller. A bigger animal is more dangerous to fight. A bigger animal has more physiological reserves for times of draught or famine. In humans, females have a strong and universal preference for taller mates (by “universal” I don’t mean that every woman prefers men who could play in the NBA, just that a general preference for height is found everywhere). But something is wrong with this picture—if size is so strongly selected for, then everyone should be tall, men especially. And while men are taller than women, there are plenty of short men around. So again, why aren’t all human males extremely tall? If women prefer tall men, then how come my shorter friends (and I’m barely taller than average) did fine in the dating/marriage market? Because all other things are not equal.

Simply put, there are multiple successful strategies in the Darwinian world. I might go for maximum size and hope that I attract a lot of mates and discourage competitors—before the next famine hits. Because when the famine hits, the short guys are going to be laughing at my massive caloric requirements (not unlike Prius owners laughing at the SUV drivers when gas was brushing $4.00 a gallon). When lots of food is rolling in, however, the big guys may go back to kicking sand in the little guys’ faces and walking off with the prettiest girl at the beach. The point is that, over the long haul, both strategies have proven successful: there are advantages to being small, and advantages to being big—in most cases of human variability, there are advantages to all of the variability we see. This applies, by the way, to intelligence, too—it takes a lot of calories to run that brain thing, and those who seem to constantly be in low power mode may have historically derived some advantages.

(Genetic heritage can interact with fertility in surprising and strange ways—although schizophrenics don’t have many children, the close relatives of schizophrenics have more than the average number; this suggests that a particular set of genes that causes increased fertility is very, perilously close to a set that induces schizophrenia. Even though schizophrenia is pretty debilitating and decreases fertility—most people prefer to mate with someone who isn’t suffering from paranoid delusions—it probably survives for this reason, always lurking around the edges of successful reproduction.)

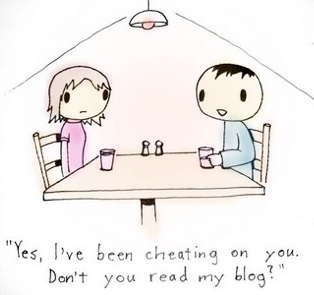

Is there an ideal proportion of big guys to little guys? Probably not, since the survival advantage of the one doesn’t particularly depend on the other. But that sometimes does happen, perhaps most visibly in the case of cheating. We don’t like cheating, of course (and actually, evolutionary psychologists have amassed evidence that we evolved our dislike of cheaters), but it can be very helpful to survival and reproduction. Imagine for a moment that you lived in an ideal world populated by nothing but the most naive imaginable dupes. In this world, no one even imagines that you might cheat; they never check, they accept any excuse… You cheat on your spouse, on your taxes, on your tests and school, embezzle from your employer, from everyone, and you never get caught. It would be nice to think that “what goes around comes around,” but not here in Dupeland! At the end of the day, you have hundreds of (mostly illegitimate) children and scads of money from all those pyramid schemes you suckered your neighbors into. Nice!

The real world isn’t Dupeland, though, and evolution has provided us with highly sophisticated cheater detectors. Just like in any arms race, we tend to upgrade our defenses when our opponents improve their offenses. Consider what would happen if everyone cheated: no one would trust anyone else. This is the Republic of Fraudistan—everyone is a ruthless, dishonest criminal. In fact, evolutionary psychologists used game theory to understand and model both of these scenarios and the results are fascinating. If you are playing a card game with a bunch of friends and you discover everyone is cheating (Fraudistan), the game is over. You won’t play any more, and neither will they. Cheating becomes perversely impossible in Fraudistan, since everyone is expecting it all the time, and constantly on guard. Your chances of getting away with it are dismally low. If no one at all cheats in a game, however (Dupeland), the incentive to cheat increases greatly: no one is suspecting it, no one is checking for it, and the chances of you getting away with it skyrocket. In short, cheating always moves to a natural equilibrium, and game theorists are able to model just where that equilibrium lies. It’s different for different games, of course, but cheating is always a minority strategy. It only works if most people aren’t doing it.

You can take that as a heartwarming lesson: most people are honest. Or as a grim prophecy: as soon as you let your guard down, others will take advantage of you and cheat you.

Now the most interesting form of cheating is, of course, sexual. And a lot of research has been done of when, where, how frequently and with whom people cheat. Some of the most interesting research shows that women may prefer to have short term liaisons (hook ups, as the kids say today) with men who are physically dominant but unlikely to stick around—the big, scruffy guy on the motorbike—but prefer the sensitive and committed sort (the uxorious, to use a wonderful and underused word) for long term relationships. They may want to sleep with Mr. Wrong, but they usually want to marry Mr. Right. Pursing those two goals under different circumstances would simply be a flexible strategy—the kind you’d expect to see evolve under Darwinian conditions. (Men appear to have a less flexible strategy—cheat whenever possible—because there is not as much Darwinian downside for them when they cheat; they don’t spend nine months pregnant, for example.) If you’re a guy, probably either gender role will “work” (pass your genes on to the next generation); they’ll just require that you put your energy and resources in different places.

So, in light of the previous post about gender roles, it may be worth thinking about gender as a strategy in a strictly Darwinian sense—it is a way of getting what everyone wants: power, fame, prestige, mates, resources, and so on. Gender roles become less of a form of psycho-social restraint (gender roles as oppression) and more a long-term strategy—like any strategy it will work out better under some circumstances than under others. Traditional gender roles may simply be a kind of majority strategy, or it may simply be that all gender roles function as successful strategies over the long run. The aggressive, assertive and forceful (more traditionally “masculine” qualities) women I know don’t seem to have had much trouble securing mates, and the more “feminine” men that I know may not have scored with the cheerleaders in high school, but they seem to have done fine for themselves over the long haul, too. If gender is indeed a Darwinian strategy, it suggests that variation in gender roles (like size) is not only natural—it’s inevitable. All natural selection works on the basis of selection over variation; there is no selection when there is no variation. This is quite different from the current view of gender in the humanities, of course—in this view gender is not a social construction nor a fictitious performance; it is a strategy for reproductive success. It is also quite different from the “conservative” view offered by Stephen Pinker in which we evolved to have traditional gender roles: evolutionary psychology doesn’t support one political orientation at the expense of another. Evolution wouldn’t have created a gender role—it would have created a strategy.

(And you’ll have noticed that I haven’t talked about homosexuality specifically yet, which presents interesting challenges for evolutionary psychology.)

The “Minority Strategy”

Cheating

is perhaps the most obvious case of a “minority strategy”—it works, but only if most people aren’t doing it.