inter alia

2/25/09

The French theorist of sound in cinema, Michel Chion, coined the term “la voix acousmatique,” or the ‘acousmatic voice,’ to describe the presence of voices in cinema that are not clearly anchored to a body in the film (the voice-over is an obvious example, although not what Chion had in mind). In general, sound in film is what we call “under-theorized”—we tend to assume it is simple and easy to describe, but in fact, ordinary cinema, let alone art cinema, does all kinds of strange things with the voice. Our dominant idea about voice in cinema is that we hear a voice, and we see a body that generates that voice, and the editing and sound synchronization make it easy to “tie” the voice to the body. They appear as a whole even though they are recorded in different registers, and are literally recorded in different locations on the film strip (and encoded with different codecs if the filming is done digitally).

My favorite director for strange sound (and Michel Chion’s as well) is undoubtedly David Lynch. Lynch loves to break up the “whole” bodyvoice in favor of bodies that are disconnected from their voices. In Blue Velvet, the main character finds a severed ear lying on the ground—but the ear appears to “hear” in several scenes. We hear sound as if from within the ear, a kind of “subjective microphone” to go along with the “subjective camera” that represents a particular character’s point of view. (YouTube doesn’t have a clip of that, but watch this from the same movie to hear sound that is not attached to a concrete body, a kind of obscene, frantic, insect gnawing that “lies underneath.”) In Mulholland Dr., we are treated to a singer giving an impassioned rendition of a Roy Orbison song in Spanish, but she collapses, unconscious, halfway through the song—and yet her voice goes on, singing and singing, relentless and unstoppable.

But my favorite example is absolutely the one from Lost Highway, where the main character, Fred, at a Hollywood party, sees the “man in black” (at 1:36 into the clip). (Warning: this is one of the creepiest scenes in cinematic history.) “We’ve met before, haven’t we?” the man intones menacingly (it doesn’t hurt that the character is played by almost-convicted murderer Robert Blake). The conversation is filled with tension-inducing, overly long pauses. “No, I don’t think so. Where was it you think we met?” “At your house, don’t you remember?” “No, no I don’t. Are you sure?” “Of course. As a matter of fact, I’m there right now.” Eventually the mystery man produces a phone and commands Fred: “call me. Dial your number. Go ahead.” Well, I’ll let you watch—and hear—how the rest of the scene plays out, but suffice it to say that it deeply problematizes the relationship between body, voice and a third element that Lynch typically introduces into his thinking through sound: a machine. In Mulholland Dr., it’s the microphone, in Lost Highway, it’s the cell phone, and in Dune (Lynch’s least successful movie), it’s a combination of the Voice from Herbert’s novel but now channelled through a kind of mechanical prosthesis worn on the wrist. Most directors try to hide the machinery for recording the voice—Lynch puts it on display.

All of this is a way of saying that the voice is free in Lynch, liberated from its ties to a single body, or even a specific organ. Voices are produced by phones, but with no body on the other end. They come out of speakers connected to a microphone, but the singer lies senseless on the stage. And a severed ear lying in a field can somehow “hear” those voices. Of course, the voices in Lynch movies aren’t free in a couple of ways—you’re supposed to pay to hear them, of course, and the overall effect of Lynch’s treatment of sound is to make the voice something inhuman, and it is invariably tied not to a body, but to a machine. It is acoustic, and yet automatic, hence Chion’s word “acousmatic,” to describe these disembodied voices.

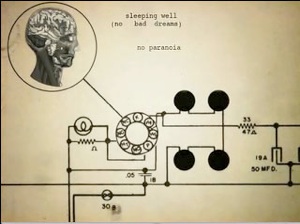

Here is the über-Lynchian icon for the program I used to record this little sample:

If I wanted to, I could add some background music, and in no time, I could create my own version of Radiohead’s song. When I do all this trickery, am I stealing Radiohead’s music? In other words, we all think we know about free speech, but is this speech free? Is text-to-speech free? Is it free speech?

As it turns out, maybe not. We own the words that we create. This blog post, by US copyright law, is copyrighted by me from the moment that I post it, even if I don’t file a claim—no one else is permitted to publish it and sell it without paying me some rights. I own the rights to my book (ALERT! First gratuitous link to my book on this blog!), of course, and I own the rights to the music I composed that I’ve posted on this blog. If I’d written a novel, no one would argue with my rights to the text of the book. And if Amazon published it in electronic format, would anyone complain if I asserted my rights to that electronic text? Of course not! I would have a right to royalties from that, too. And the audiobook? Well, sure—the publisher, the person who reads the book and I should all get royalties from the audiobook. Especially since Americans don’t really read any more, and audiobooks are one of the only growing segments of the publishing world. Right?

So I should pay three times for all the versions of a book: once for the paperback, once for the ebook, and once for the audiobook? Hmmm. This is starting to sound like the problems that computers created for the music and movie industry. Should I pay once for the DVD, and once again for the version for my iPod? That’s not free speech, is it? I make my own iPhone versions of my DVDs using Handbrake, and no one is going to take me to court over that—but it goes without saying that the movie industry would prefer that I pay, pay again, and then pay again. (They’d actually prefer that I pay every time I watch—or even think about watching.) The industry actually does not recognize my legal right even to make a backup copy of the movies I’ve purchased, let alone to convert my DVDs into different formats.

What brings this to a head is that the new Amazon Kindle can read your ebooks out loud to you, probably with an electronic voice at least comparable to “Alex.” And writers are not happy about it. The machine makes an audiobook out of an ebook, but only pays one royalty to the author. I’m actually completely in favor of this, for various reasons that I’ll outline in the next post, but I think there’s a really convincing argument in favor of restricting this “free speech.” If you want a nice presentation of that argument, check out Roy Blount’s OpEd in the New York Times today. He calls it—rather cleverly, and isn’t that why artists deserve our money?—the “Kindle Swindle.”

Free speech (part I)

AAAAAAAAAAAGHGGGGHHHHHHH!!!!

The sound of a writer without royalties.