inter alia

3/30/09

Most classic paintings of the “music lesson” topos are of women or girls. Here are some typical examples, culled from Google’s image search:

They remind me of all of the 18th and 19th century paintings of women reading (see here and here and here and here and here). In both cases, I think the pleasure that the painting affords is rather voyeuristic, if not quite pornographic (although the last two images of music lessons above certainly suggest a seduction that is part of the pedagogical act, and Google image search will come up with some “music lesson” results that are more clearly pornographic). We’re seeing an intimate moment in the life of the upper-middle class woman—intimate, but also vital. A woman’s eligibility, as all those who have read Jane Austen will recall, was really determined by her fortune, her looks, and her “accomplishments.” Practical domestic abilities, like embroidery, were all very well, but to indicate that she had really massive amounts of leisure time, she should really have devoted herself to purely “ornamental” arts. Of those, drawing was important, but music was far more so. Especially the piano, of course, since the piano came to embody pretty much all middle-class aspirations by the start of the 19th century.

(By the way, I find it simply amazing that middle-class girls today are still educated in the same three ornamental “accomplishments” that were a fundamental part of the typical middle-class aspirational woman of Austen’s time: piano, dance, and (somewhat optionally) French. I think these are all good things, of course, but all those piano lessons and ballet recitals are really relics of a previous era—actually, several eras earlier! But this also raises the question: when will Renée begin Rowan’s piano lessons? Do not ruin your daughter’s martial marital prospects, Madame!)

Anyway, I just finished Pascal Quignard’s La leçon de musique (The Music Lesson), and although the little fellow has long hair, it appears to feature a rare scene of a young boy’s music lesson. You can see the gender differences right away of course—the boy is looking directly at the viewer, so there is no voyeuristic element; the hand on his shoulder and the hand turning the page are both male hands; he is reading sheet music rather than playing (it is sheet music, by the way—on my cover I can see the staves and notes); and unlike the women playing, who are absorbed, rapt, or transported, the young boy looks rather bored, frankly. The image is from a painting in the Louvre (I’ll have to look it up next time we’re there) by Valentin de Boulogne, who rather specialized in paintings of musicians in the 17th century, and the whole context shows that the boy is surrounded by musicians. Quignard, like Calvino, was an editor for a long time, and I expect he chose the cover, and chose it with great care. It’s by a French painter, it shows a music lesson in progress, and it’s quite crucial for his book that it should show a pre-adolescent boy. Why?

The book is somewhere in between fictional narrative, essay, and a kind of historical documentary. (I should say—since I’m going to go on to critique and possibly even mock it—that I quite liked it, and am planning on reading more of his stuff.) Quignard is from a family of musicians and grammarians, so he ended up with a tremendous desire to write about music, and an ability to read a lot of languages (ancient Greek, Latin, Chinese—you know, the easy ones). The book is divided into three semi-biographical sections: the first and longest is on Marin Marais, the French composer who would be the subject of Quignard’s most successful book (Tous les matins du monde, 1991, which was also turned into a movie with, of course, Depardieu); the second section is about Aristotle; the third about the Chinese musician Ch’eng Lien. Each section consists of a series of smaller or larger fragments, reflections, or observations, all linked around the same themes: the voice; the breaking of the voice in adolescence; the bodily changes in adolescence (the “mue,” a word that refers to any of the radical changes of the body, from snakes shedding their skin to the breaking of the voice in puberty—molting, breaking, sloughing off, metamorphosis); death (whose arrival is indicated by the onset of adulthood—again, the breaking of the voice); and the relationship between music and time. Does music postpone time? Play with time? Eliminate time?

If there is an “argument” to this book, it would go something like this: music is the breaking of the voice—the shift downward in timbre and register that indicates both our eventual descent into the grave (paralleled by a third descent as well, the descent of the testes; but Freud also thought that the arrival of adult sexuality was tantamount to the arrival of death), as well as our way of avoiding that death, of playing with temporality and loss, endlessly forestalling it. Quignard always discusses the mue as a loss, and suggests (hmmm, there appears to be some Lacan here…) that the breaking of the voice splits the speaking subject forever—the voice of childhood, and the adult voice. He writes:

Men lose their childhood voice. They are beings with two voices—a sort of two-voiced song, if you will. They can be defined, after the onset of puberty, as: humans whose voice deserted them in a metamorphosis [mue]. In them, childhood, non-language, the real—this is the skin of a snake.

*

Two possibilities. 1) Castration. Their childhood voice remains. Their balls are cut. Sacrifice and a foreign realm. 2) Music. They attempt to metamorphose the metamorphosis itself [muer la mue même]. They become composers or instrumentalists. They work on a voice that will not betray them.

Quignard has a lot of very beautiful, suggestive claims to make about music here. Many of them are perfect epigrams for someone writing about music (“the invention of melody is not human, and precedes human time”). They’re all suggestive and somewhat enigmatic. It’s also full of fascinating and unexpected links—for example, the Greek word for tragedy, tragôdìa, literally means “song-of-the-goat.” This probably referred to ritual animal sacrifices at the beginning of the performance, but Quignard also links this up to the goat-like bleating of the breaking male voice in adolescence (which is how Aristotle refers to it), and well as the weeping voice, broken by loss, by tragedy.

That doesn’t change, of course, the sexism—fortunately, Quignard comes right out and says it. Sure, he figures this breaking voice as a tragedy:

The voice is faithful to women. The voice is unfaithful to men. A biological destiny subjected them, at the very heart of their voice, to being betrayed. To being abandoned. To metamorphose. To change.

What a tragedy, to be subjected by biological destiny to music and composition (and writing, and art, and architecture, and—well, all of human culture). Women, of course, are not subjected to this tragedy, to this split subjectivity—that may sound like it makes them whole, but what it really does, of course, is make them flat. They become characters without psychological depth, flat screens that we can look at for our enjoyment, but that do not look back (as is the case with the paintings that I started with). And indeed, Quignard comes right out and says that women are not composers because they “live and die within a soprano that is indestructible.” It’s a great phrase, but I can’t accept the premise.

It’s not that I don’t think there are biological and psychological differences between the sexes—I think evolutionary psychology is a tremendously powerful (albeit sometimes dangerous) tool. Among other things, evolutionary psychology strongly rejects the idea that biology is destiny. At most, biology is tendency, a predisposition, a statistical likelihood. But Quignard’s kind of psychoanalytic thinking about sexual difference effectively turns these differences into foundational myths, things that are true beyond time—we could say that they become metaphysical truths. Or maybe I just find the idea ridiculous: I don’t miss my childhood voice; I’ve never once heard anyone complain about it or describe it as a loss (this would not be true, of course, of professional boy singers). I think sex and sexuation are hugely important for our psychology—but I’m more dubious about the importance of vocal register for it. In general, the attempt to parallel the descent of the testes and the descent of the male voice seems like a forced analogy for which I would mark an undergraduate’s paper down, no matter how elegantly Quignard pulls it off.

But here’s the thing. I realized that while I could name any number of female writers or painters (and even architects, mathematicians, etc.)—I don’t know a single female composer, either historical or contemporary (gazillions of super talented female musicians, but no composer). I listen to a lot of classical music, and it seems like I ought to at least know the exception that proves the rule. Shouldn’t there be the one female composer whom everyone knows? I have no doubt that there is one, and probably many. Why don’t I know them? Why didn’t the same reformers bent on revising the literary canon when I was Santa Cruz also tell everyone about Ludovica von Bettyhoven? Where is music’s Artemesia Gentileschi, or Aphra Behn? I’ll go and look it up on Wikipedia now, but I’m curious if any of my readers—Alice?—know any female classical composers. I mean, of the sort where one might one day hear one of their works performed, live or on the radio.

UPDATE:

First, Alice’s link deserves to be included in the main post, especially now that she’s reading Heloise and Abelard (given the centrality of castration to Quignard’s thinking about music).

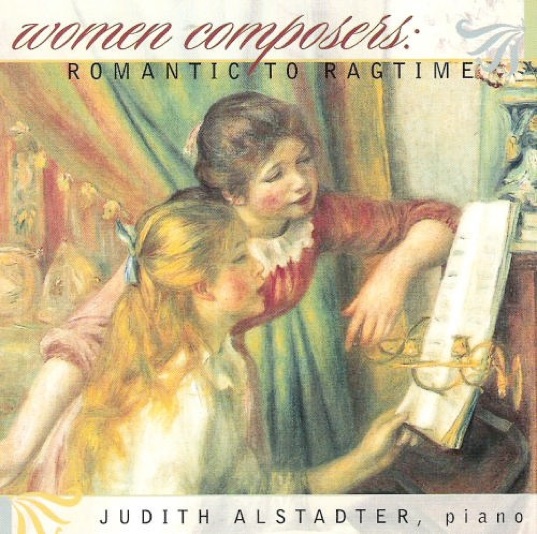

Second, I wanted to see if Clara Schumann’s works were available in a relatively mainstream recording. The iTunes Store indicates that there are four or five recordings largely dedicated to her work, and at least one of them is on a label (Hyperion) that I’ve heard of before, so I’ll say that counts. But the main hit on iTunes is to this album below, whose cover art, happily, features a classic 19th-century painting that manages to combine the “music lesson” topos with the “woman reading” topos (and it’s by my favorite painter, too). I will say that it most certainly does not feature a scene of “composition”:

listen to the album for free at deezer.com

La leçon de musique (UPDATED)

Every now and then

my voice breaks, even now that I’m forty. I still have acne. I think I’m doomed to live the rest of my life in puberty.