Yesterday I took the afternoon off to see the latest Miyazaki (partly because I like the others that I’ve seen, and partly to see if Sasha could watch it), Ponyo sur la falaise here in France, or just Ponyo as it will be known when it comes out in the US later this year (it seems that English, unlike French, Italian and Japanese, doesn’t have a word that means “cliff that overlooks the sea”). [See comments below]

There’s a real pleasure to seeing Miyazaki’s films (actually, there are several), but it isn’t a narrative one. Other films might hook you by posing a seemingly intractable problem for their characters and spiraling out the consequences of that problem and its eventual solution for the next two hours. That’s narrative. Miyazaki’s narratives are often weak, however: if I think about Porco Rosso (which I’ve seen—thanks to Sasha—about 150 times), there are a series of problems, but there not really interrelated, and some (like the Italian fascists pursuing Porco) just drop in and out. When the fascists appear, they’re really just there to move Porco to the next scene. In part, this weak narrative is at least partly due to Miyazaki’s missing villains: in Porco Rosso, everyone turns out to be pretty much good, even the loudmouth American, Curtis—even the air pirates, who turn out to be rather charming and lovable. And in fact, the only Italian fascist we every really see, Porco’s old friend from World War I, isn’t so bad, either. It’s the same as the universe of Star Trek: there are no bad guys—just misunderstood good guys.

That’s true in Ponyo, as well. Miyazaki moves through a series of loosely related sequences, often relying on deus ex machina (quite literally in a couple of instances, but more dea ex mari than deus ex machina) devices to get from one to the next. And while there is a character who is an antagonist, he is not a “bad guy”—his faults include being overprotective and wearing way too much eye makeup. No narrative, and no confrontation? Where’s the pleasure in Miyazaki again?

One source of pleasure is, of course, familiarity. Miyazaki is an auteur, a director than one recognizes not only by the drawing style, but by certain themes, episodes, moments. Watching

Ponyo was like greeting a series of old friends from

Porco Rosso and

Nausicaa, only wearing different clothes. For example, Miyazaki—in a really excellent sequence—has his characters communicate across the open sea by using lamps with shutters that can be rapidly opened and closed (as in

Porco Rosso). Wikipedia informs me that this is called an

Aldis Lamp. The wife is on land (furious because her husband has had to leave on another trip and won’t be coming home for dinner) signaling to her husband on the ship he’s commanding. It’s nighttime and one can barely make out the seascape and the vessel. Their son begins to communicate and asks his mother what he message he should send.

She carefully spells it for her son, who dutifully flashes out: “C. R. E. T. I. N.” The audience laughs, of course, but the husband responds instantly: “A cretin who loves you,” and as he sails off, the light from his Aldis Lamp pulses slowly and rhythmically, a tiny light on the side of the ship, no longer in code, once, twice, and then: then the entire ship lights up in a blaze of yellow, red, green, blue, a surprise Koichi has prepared for his wife and son…

The husband-wife conflict isn’t a serious issue in the film, the way it would be in another filmmaker’s movie. It’s a funny way for Miyazaki to get to do what he wanted to do in the first place—go back to his favorite signal lights with shutters. He must have seen them when he was a child, and they seemed like magic to him. And of course, they still seem like magic to children today, and that’s what Miyazaki wants—to return to the viewer than magic of childhood. In Ponyo he takes that magic and adds his pulsing, altogether unexpected light show. It is these little obsessions that return again and again in Miyazaki that I like—the smaller the better. I get bored when someone always comes back to the same Grand Themes, but I find Miyazaki’s shuttered signal lights irresistible. (To take an even smaller example, a shot of the empty beach at night—the waves wash in and wash out. Any other animator would stop there, but Miyazaki always makes sure to show that the sand is darker now where the water was—dark from the damp.)

But if familiarity is one source of pleasure in Miyazaki, the other has to be defamiliarization. And

Ponyo has plenty of that, too. Animation, of course, can show us things that could never be, but it shows them in a way that does not break the “reality” around them. In ordinary film, whenever there is a “special effect,” we are aware of its “special” status, no matter how perfectly it is done and integrated into the film, because we know that in the real world, people cannot levitate, or turn into tigers, or suddenly grow an extra arm. But there are no “special effects” in an animated film—the reality is all of one piece. This is one of the reasons I think Miyazaki is right to resist computer animation and insist on drawing by hand: there are no technical limitations, and hence no sense of special effects.

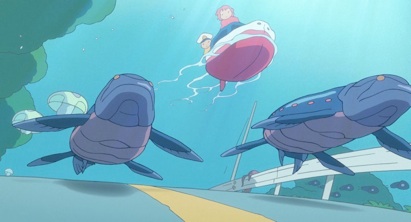

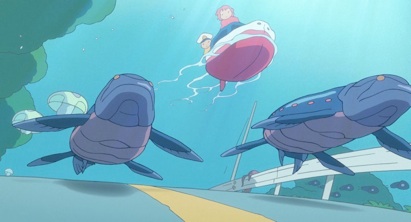

And so Ponyo can show us a remarkable world that is filled with enchantment both mundane (Ponyo repairs a broken electrical generator) and awesome—the sequence in which Ponyo and Sōsuke sail over crystal clear waters that now cover Sōsuke’s village is particularly so. Enormous prehistoric fish swim along the highway, while an octopus climbs into a house through an open window. That sequence is one of the longest in the film, and deservedly so—the hectic human world is transformed into a slow-motion, three-dimensional space inhabited by creatures from another world. Indeed, the defamiliarization of the terrestrial world by flooding is itself a familiar gesture in Miyazaki:

Spirited Away, Cagliostro, Ponyo.

The movie (

Ponyo, that is) is loosely based on Anderson’s

Little Mermaid—I should emphasize that the adaptation is very loose. It would nonsensical to compare it to the Disney version of course, but difficult even to compare it to the original story, other than to note that it is happy, exuberant, chaotic and beautiful. It has a few faults of course. If you have ever seen Cameron’s

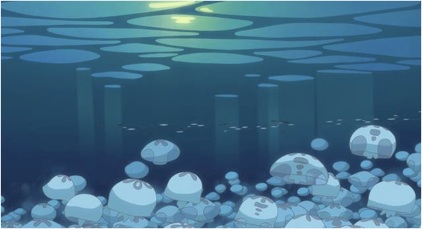

The Abyss, you’ll know that there is an odd temptation in underwater films to become “wonderbound,” stuck in a permanent, slack-jawed rapture over enormous, multicolored, phosphorescent medusae hovering over crystalline coral reefs and whatnot. It is one of the last refuges of a pure, unalloyed Romantic sublime—the confrontation with an aesthetic enormity, so monstrous and otherwordly as to reduce the poet to silence. Or, in the case of filmmakers, to seemingly endless, static sequences of giant, glowing multi-colored jellyfish surrounded by rainbows.

Miyazaki goes there a little bit. There are two rather superhuman characters, and one of them is so powerful, mystical, nurturing and good that it’s rather cloying. Still, he tells a totally non-icky and completely believable love story that takes place between a girl (sort of) and a boy who’s about seven years old, and you have to give him major props for that. It’s the real love that children can have for each other (or for animals, or even inanimate objects), not the fake kind you usually see in movies, the kind completely informed by adult love, filled with winks and blushing. Perhaps that’s the most astonishing thing that Miyazaki does. He depicts a world of love without embarrassment. It’s a bit of surprise, even for the characters themselves sometimes.

Also, Miyazaki’s children are always very polite. It’s not didactic as it would be in an American film. That’s just how his world is. Full of love, polite children, signal lamps, and flying machines.

Sigh.

PS

Berlin photos are up for Day 2: Potsdamer Platz and Playpens (and missing wallets and passports, but we’ve already covered that ground)