inter alia

4/1/09

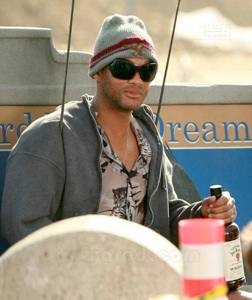

I just watched Hancock, because that’s about how behind things I am. I remember reading several nuanced reviews of the film, and now I see why. Will Smith is as winning as ever, Jason Bateman plays the same sort of straight man, heart-of-gold doofus that he played in Arrested Development, and Charlize Theron alternates between looking incredibly beautiful in a MILF-next-door kind of way and pretty awful in a I’m-about-to-die kind of way. Which is what she’s good at, I guess.

The film is often funny in its deflation of the superhero conceit. Hancock is a super-powered superhero, but he’s also an abrasive, drunk, homeless superhero (the characters in the film prefer just to call him “an asshole”). He stops the bad guys, but often at the cost of tearing up several city blocks in the process. The mayor asks him to leave the city (and worse still, he asks him to go to New York—there’s no worse insult in L.A. Except for maybe “San Francisco”). There are funny exchanges like:

-

Ray: So, you’re from another planet?

-

Hancock: No, man. I’m from Miami.

Still, there are some signs that all is not well in the world of Hancock. In one scene, for example, the reformed Hancock arrives at the scene of a crime to rescue a wounded female police officer. (Piling it on thick, the TV broadcast we can overhear informs us that she is the widow of an Iraq war veteran with two kids.) The cleaned-up Hancock stops and asks:

-

Hancock: [to pinned-down cop] Good job! Do I have permission to touch your body?

-

Cop: Yes!

-

Hancock: It's not sexual. Not that you're not an attractive woman. You're actually a very attractive woman, and...

-

Cop: [screaming] Get me the hell out of here!

It’s obviously played for laughs, but it’s less funny if you notice all the interactions between Hancock and Ray’s hot blonde (and very pale) wife. The film, at least the theatrical release, doesn’t seem to like the idea of Hancock being sexual (no Hancock groupies?). Especially not with Ray’s wife. Whoa! Smoldering glances, then more smoldering glances, then inexplicable hostility, then strange silences, sidelong looks—what’s going on here?

What’s going on is the big twist in the plot, which is nicely unexpected and almost enough to save the second half of the film. But it was at about this point that I realized the film had three characters: Black Man (Hancock); White Man (Ray); and White Woman (Ray’s wife, Mary). And that’s about the point that I realized that Hancock is not a deconstruction of the superhero movie at all. It is instead a racial fantasy about giving the American black male a makeover. And it’s not just any makeover. It goes like this:

-

•Black Man learns that White Man is goofy and awkward, but really nice, and with Black Man’s best interests at heart.

-

•Black Man learns to shave and make himself presentable.

-

•He learns to wear a suit.

-

•He learns to go to prison and stay there until his time is up.

-

•He learns to speak English correctly, like White Man tells him to (this mostly involves learning to say “please,” “thank you,” and “good job,” to people who have tried to help.

-

•He learns to stop drinking.

-

•He learns to control his anger and resentment.

-

•He learns to stay away from White Woman (in fact, in an oh-so-scandalous turn, we learn that he and White Woman have been together before!)

-

•But (he learns), if he and White Woman ever do get together again, he will die.

Now how’s that for the white man’s racial fantasy? It acknowledges interracial attraction, but places under a kind of metaphysical threat of death (oh, no! It’s not that lynch gangs will kill you for touching my wife—it’s just the way that the universe is structured: if you get near my wife for too long, you will die! Sorry! I really just have your best interests at heart!). It shows the Black Man how much happier he would be if he just shaved, stopped drinking, spoke politely, wore a suit, stayed away from white women, stopped being so resentful, and showed himself to be appreciative of all the help we’ve given him over the years. And really, is that too much to ask?

As it turns out, it’s not enough to ask. The film has another sacrifice to ask of Hancock (well, really, to demand of him—but let’s not quibble). I mentioned that the film has essentially three characters: White Man, White Woman, and Black Man. You may have noticed that a term is missing here in our semiotic square. There is no Black Woman. There is no one for Hancock to be with (accepting the film’s premise that interracial couples are totally forbidden by the structure of the universe), and he willingly accepts this fate of eternal loneliness at the end of the film, and accepts a self-imposed exile in New York. Self-imposed, ageless isolation for all eternity? No possibility of a partner, ever? Strength and power beyond that of mortal men? Where have I heard those themes before?

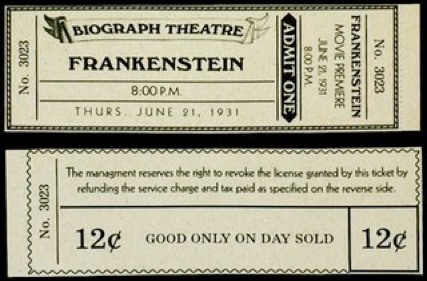

The film tells us the story of Hancock’s origin, such as it is: Will Smith’s character woke up in a hospital with amnesia and super-strength (he’s ageless, too—this was over 80 years ago). In his pockets, he has only a stick of gum and two movie tickets. No one stepped forward to claim him—no family, no friends. The only important bit of information in all this distracting emotional rubbish, of course, is the title of the movie he was seeing on the night he became “Hancock” (the discharge nurse asked for his “John Hancock” on his way out, and, having amnesia, he assumed that was his real name). What was that movie? Frankenstein. No family, no friends; self-imposed, ageless isolation for all eternity; no possibility of a partner; strength and power beyond that of mortal men. Right. That’s where I’ve heard those themes before.

Hancock

Strange…

Will Smith doesn’t look like a monster.