inter alia

8/1/09

UPDATE: I’ve fixed some display issues with this with the later images.

One of my most memorable movie-going experiences was Treasure of The Four Crowns (1983) in 3D. It was the only 3D movie to be released in my neck of the woods that I knew of growing up. And I didn’t see very many films (Logan’s Run, Star Wars, The Life of Brian, Romancing the Stone, ET, Raiders of the Lost Ark, Back to the Future, Treasure of the Four Crowns, Star Trek: The Motion Picture, The Empire Strikes Back, and the last, horrible Star Wars movie, plus a handful of others: there was some Harrison Ford legal drama—oh, and The Big Chill). Anyway, Treasure of the Four Crowns is a famously terrible movie, but it was extremely enjoyable thanks to an incredibly talented heckler somewhere in the back and on the left. I think he may have been kicked out near the end, but he really made a dreadful film worthwhile—sort of MST3K avant la lettre, if you will.

The film was in 3D, which meant that, at every opportunity, someone jabbed, hurled, or otherwise protruded themselves or some object at the audience. 3D is bizarre in that it really does appear to protrude well beyond the screen, sometimes appearing to nearly graze the audience—it was often used for objects that were clearly, realistically, only a few feet long. But when they were pointed at the audience, they were clearly, suddenly, 40 or 50 feet in length. It looked bad, it looked ghostly, and objects in motion blurred in an unpleasant way. The film, like many 3D films, had no other raison d’être: the plot, the characters, the action, etc—everything existed only in order to showcase the miraculous three-dimensional photography. I have written about such “film in the service of the marvelous” before, and tonight I am honored to report that Treasure of the Four Crowns is not only a horrible movie: it is also a peplum! Literally. It was directed by Francesco Baldi, a well-known peplum, spaghetti Western and Italian espionage director.

Anyway, I’m thinking about Treasure because I just went to see the latest Pixar release, Up, in 3D. The new 3D. The new 3D uses differently polarized light rather than red and green, and the quality is superior: not ghostly, not blurred. Up, as one would expect from Pixar, made subtle and appropriate use of its 3D—it basically gave an additional sense of depth. I say additional because, of course, conventional film uses all kinds of techniques (especially depth of field) to convincingly present the illusion of depth. 3D convinces you that there is depth because of parallax—your left and your right eyes see slightly different scenes in real life, because they are a few inches apart, and the amount by which the two scenes differ allows your brain to unconsciously infer the distance of the object. If you move your head from side to side, nearby object appear to move a lot; distant objects hardly at all (this, by the way, is why the moon appears to “follow” you when you drive at night—it’s too far away to shift position as you move). In any event, despite the significant advances in 3D, it is still nothing like seeing actual objects arranged in space, and it has other problems as well.

Many people assume that we primarily experience depth because of our binocular vision, but it turns out that that’s only a part of it. Our brains use cues from shading, lighting, size, expectations, and even proprioception, our sense of where we are and how we are moving, to build up an overall sense of how far away something is. As a result, even the new 3D cinema appears unpleasantly strange at times, even alienating, because it looks more like a simulacrum of three-dimensional space, an imitation of it. It may sound strange, but because of this “imitative” quality, I generally had the impression of three or four clearly defined planes of distance, but no sense of gradation between each plane. They looked like the old backdrops in Hollywood films made on studio lots, like the Wizard of Oz, only with the weird look of a Viewmaster slide.

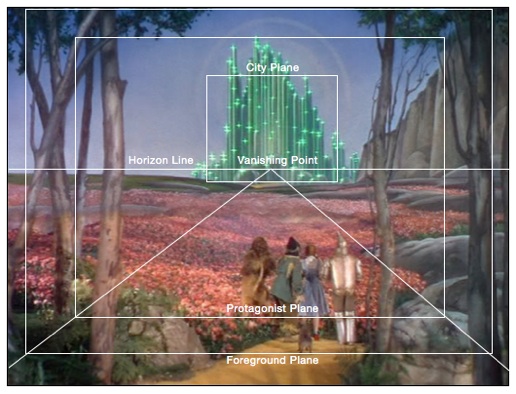

There’s a clear foreground of rocks and trees, a middle plane of our four and a half protagonists, and one or two flat, painted backdrops of rocks, poppies, and a distant emerald city. That’s what the 3D looks like to me, only slightly more unpleasant and uncanny. In other words, 3D manages to achieve an impressive feat: it looks flat. Indeed, it looks more flat than an actual flat screen.

Most of the previews we saw were in 3D as well, and they were gimmicky and false, making cartoonish use of the extra depth. The audience reaction was laughter and snickering, and it was not kind laughter. One had the experience of a novelty, just as in the 1950s. That’s bad news for theaters that are hoping this new wave of 3D will save them. Theaters are in big trouble, because home theaters with Dolby 5.1 sound and huge, vivid flat screens showing high definition are becoming more and more common. 3D holds out the promise of something that will entice people off of the couches and back into theaters—but I’m dubious. The 3D worked best when it was used subtly—but then I didn’t really need it at all.

Another problem with 3D has to do with the nature of a screen. A screen functions as a bounding space, a frame for the image. Now, because 3D in cinema uses parallax, it can send whatever signal it wants to the audience about distance. It can tell you that the object is two feet in front of you, creating alarming moments when an object looms, veers, plunges or leaps out at the audience. So it can place the apparent distance well in front of the screen. It can also place objects “behind” the screen, which is what traditional cinema does with size, shading and focus. Look at the image from the Wizard of Oz again: you can immediately tell that the principal characters are standing about 12 feet “in” the screen space, that the tree on the right hand edge of the frame is “at” the screen distance, or that the backdrop starts about forty feet “deep” in the screen space (and that the Emerald City is perhaps a mile distant). If I may draw a diagram of the traditional rules of screen space in traditional cinema:

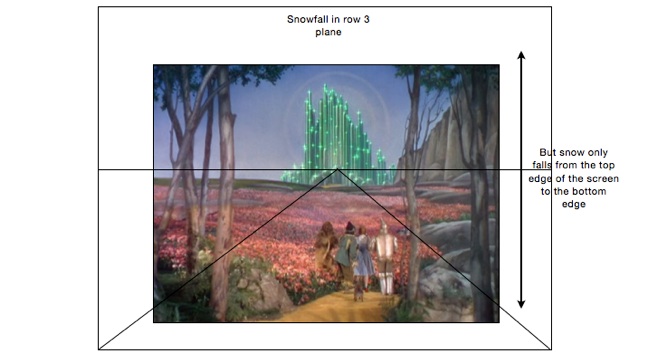

Obviously, they’re the same as traditional painting. The key here is that they work perfectly within a limiting frame. The frame represents the logical edge of possibility for representing space. What happens when you represent space that is closer to the viewer than, say, that tree on the right hand edge? Such space exists. What if, say, snow were falling (as it does a few moments later in the Wizard of Oz): it will fall within the “Protagonist Plane,” it will fall on the Foreground Plane—it will fall everywhere. Including closer to us than the edge of the screen. What we will see are blurry flakes passing right in front of the camera lens. And that’s okay. It looks good. It maintains the intensely voyeuristic illusion of traditional cinema—this is precisely the view one would expect peeping through a keyhole. You have the effect of a fixed place and a bounded field of vision, a frame (the keyhole).

It looks terrible in 3D.

Here’s why. You see how, in the example above, each plane is smaller, receding into the distance and the vanishing point? Snow falling in the protagonist plane, for example, will hit the ground at Dorothy’s feet. And snow falling on the horizon will hit the horizon. Well, the 3D planes that come out toward the viewer should get bigger as they are closer to the viewer than the screen—and, of course, they don’t. They can’t. Snow falls, apparently in the third row of the theater—wow, what a novelty! Except that instead of landing on the theater floor, the snowflakes vanish when they hit the bottom edge of the screen. Of the screen, not the plane of depth to which they should belong.

It ruins the illusion of three-dimensionality. If the perspective of a traditional vanishing point tends to literally draw the viewer into the screen, make you get lost in the illusion, then 3D’s failure has the opposite effect: it makes it clear that there is an illusion, and that there is an insuperable gap between the audience and the screen/frame. 3D attempts to fill the space between the viewer and the screen with fictive objects, making an unbroken continuum between the real world of theaters and seats and the fictional world of the film. But in the end, it produces an uncanny valley in which the viewer is constantly aware of being manipulated. The space is filled instead with impossible objects—snow that disobeys the laws of perspective and optics. It might as well be one of those blurry, suddenly forty foot swords from Treasure of the Four Crowns.

(Oh, and to add to my list of movies I saw in the theater from age 6 to 18: Bachelor Party.)

3D (updated)

Laugh it up

Fuzzball.