Course Description and Objectives

Archaeologists investigating sites of craft and industrial enterprise often puzzle over a domain of bewildering ruins. Locations of remarkable energy, tumult, and creativity stand silent. This course provides an overview of the archaeology of American craft and industrial enterprises, outlines developments in theories, research questions, and interpretative frameworks, and presents case studies from a wide range of subjects.

Research focused on industrial enterprises ("industrial archaeology") traverses a spectrum of perspectives. Some limit their efforts to recording, mapping, and studying the mechanics of a site. Others examine comparative questions of changes of technologies over time and space. Many analysts look away from the buildings and equipment of the workplace and focus instead on the workers, their families, residences, lifeways, and health experiences. With many sites presenting standing ruins, historians and archaeologists often encounter local stakeholder groups who wish to promote heritage themes and tourism potentials.

This course covers a range of topics within industrial archaeology that relate to core principles of the field of archaeology: methods of investigation, interpretation and modeling of results; archaeological ethics and cooperative project designs working with local and descendant communities concerned with the heritage of the archaeological remains under study; and strategies for protecting the cultural resources manifest in those cultural landscapes. The course will also provide students with opportunities to learn fundamental archaeological skills such as surveying, sampling strategies, remote sensing, applications of GIS to archaeology, and the creation of interpretive frameworks for a public audience.

By the conclusion of this course, each student should have acquired skills in the following areas: understanding the theoretical and methodological principles utilized in conducting industrial archaeology studies and the interpretations of data produced in such projects; critical reading and assessment of particular industrial archaeology studies and the basic assumptions, theories, and methods utilized in those studies; an enhanced ability to communicate in written and oral form a research design and interpretive framework for an archaeological site; enhanced skills in locating and utilizing sources for industrial archaeology, including those available through libraries, the internet, research groups, and professional organizations.

The course is organized around reading, class presentations, and critical discussions. Responsibilities for leading discussion of the readings will be rotated among class participants. There will be occasional lectures to offer background on theoretical issues and particular methodological topics. The quality of your course experience will depend in large part on your willingness read thoughtfully and participate actively in class discussions. This course will provide you with the opportunity to hone your skills in articulating significant arguments presented within a particular range of archaeological studies. The course also provides a supportive environment in which to practice your skills at written exposition, classroom debate, and public presentations. This is, for the most part, a reading and discussion course intended for advanced undergraduate students and and graduate students with backgrounds in anthropology, archaeology, engineering, history, material science studies, and landscape analysis.

Graduate students, who receive the equivalent of four credits or one graduate unit, will be expected to produce seminar papers of greater length and depth of analysis than undergraduate participants in this course. Graduate students may also arrange to meet with the instructor for additional discussion times each week. For undergraduate students to enroll in this course, they should have already taken an introductory archaeology course, such as Anth. 220. Learn more about the course structure and opportunities in the general syllabus guidelines.

Locations and Instructor Background

The class meets on Wednesdays, 3pm to 5:50pm in Davenport Hall (room to be determined). Instructor: Chris Fennell, office in 296 Davenport Hall, cell phone (312) 513-2683, email cfennell@illinois.edu. I specialize in historical archaeology as a Professor in Anthropology and Law at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. My empirical research addresses subjects in trans-Atlantic historical archaeology and the dynamics of social group affiliations and lifeways among Europeans, Africans, and various social groups within the Americas. These research initiatives include interpretative frameworks focusing on social group identities, ethnic group dynamics and racialization, diaspora studies, regional systems and commodity chains, stylistic and symbolic elements of material culture, consumption patterns, and analysis of craft and industrial enterprises.

Required Readings

Texts

The Archaeology of Craft and Industry, by Chris Fennell (University Press of Florida, 2021).

Print copies of this book are available through online stores and will also be available through the UIUC Library Reserve system.

Additional suggested readings: Perspectives from Historical Archaeology: Investigations of Craft and Industrial Enterprise, textbook compiled and edited by Chris Fennell (Society for Historical Archaeology, 2016) (pdf of chapter titles and abstracts).

Readings on Electronic Reserve

The other readings listed below under each week's discussion topic, consisting of articles and excerpts from other texts, will be available on electronic reserve in the course web site available through the University's Canvas program.

Enrolled students can access the course web page by logging onto the Canvas system, which will display all existing web pages for your courses. Choose Anth. 399 from the display list and you can access the course syllabus, assignments, lecture notes and illustrations, and other online class resources for Archaeology of Craft and Industry.

Additional Resources

I have also compiled a broader list of published studies and internet resources on industrial archaeology (link) which may be useful in choosing a paper topic, conducting research, and further exploring related subjects.

Course Assignments and Grading Policy

Your grade in this course will be based on your performance in completing the following assignments:

1. Lead Discussants (10 percent of course grade). Class participants will be responsible for leading discussion on the assigned readings for selected class meetings. Such lead discussants should not simply summarize reading assignments one by one, but rather highlight significant theoretical and methodological themes that emerge in the articles, the manner in which they relate to one another and to previous topics discussed in the course, and their implications for industrial archaeology analysis. For example, one should address questions such as: Do the researchers' positions agree? Do you find their arguments persuasive? How do they fit (or fail to fit) with other anthropological and archaeological ideas you find helpful or attractive? A key focus of your presentation should be the manner in which abstract theoretical models can actually be implemented in studying the archaeological record. If particular patterns in industrial remains (the built environment, objects, machinery, and impacted landscapes) are discussed and explained in an assigned reading, can you think of other ways to account for them? Your presentations should also include a series of questions for discussion by other participants in the class. A sign-up sheet will be distributed for you to choose those weeks in which to be a lead discussant.

2. Class Discussion (10 percent of course grade). Those students who are not a lead discussant in a given week should still come to class prepared to discuss critically the week's readings. I also reserve the right to lower the course grade (by one letter grade) of any student who fails to regularly attend class during the semester.

3. Short Essay (20 percent of course grade). In the eighth week of the course, participants will complete a 5-6 page (double spaced text) introductory essay entitled "What is Industrial Archaeology?" and present a short oral synopsis (5-10 minutes) in class. In writing the essay, you should draw on the assigned reading, class presentations, discussion, and your own insights. This is a first opportunity for you to outline your vision of just how industrial archaeology is a distinctive enterprise in the theoretical, methodological, and empirical realms. The short essay and the oral presentation based on it are due in class at the beginning of Week 8 (Oct. 16). After revision, this short paper can become the introductory section of a longer seminar paper (see below). The grade for the short essay or final seminar paper will be reduced if a student submits the completed assignment late (by one letter grade for each day it is late).

4. Seminar Paper (50 percent of course grade). During the last two to three weeks of the course, participants will complete drafts of their seminar paper, which should be 15-20 pages (double spaced text) in length for undergraduates or 20-25 pages (double spaced text) in length for graduate students. In the seminar paper, you will explore a particular aspect of industrial analysis that interests you. Your paper can have a theoretical (e.g., industry and sustainability), methodological (e.g., sampling strategies, LiDAR surveys, and GIS), or substantive focus (e.g., particular industries like pottery, iron, or mining). This is your opportunity to explore in greater detail a subset of the theoretical and methodological ideas encompassed by industrial analysis. A revised version of your short essay ("What is Industrial Archaeology?") can serve as the conceptual foundation for this effort and as the introductory section of your seminar paper. The focus of the rest of the paper is up to you, but it needs to be cleared in advance with the instructor. An abstract or preliminary statement, with key bibliographic references, is due in class at the beginning of Week 11 (Nov. 6). The final seminar paper is due by 4:00pm on Dec. 20.

5. Seminar Paper Presentation and Discussion (10 percent of course grade). During the last two to three weeks of the course, each participant will present in class a 15-minute synopsis of the seminar paper. This will be followed by 10-minute evaluation and comment by a designated discussant. Following a response by the author, the floor will be opened to general discussion. Drafts of the seminar paper will be distributed one week before this presentation to all class members, including the designated discussant.

When preparing these assignments, be careful that you do not plagiarize the works of another; that is, do not present the work or words of another author in a verbatim manner as your own. Consult the UIUC regulations for more information on the hazards of plagiarism, at http://studentcode.illinois.edu/.

Class Schedule

Week 1. Aug. 28. Course Introduction

Overview of course, spectrum of industrial archaeology subjects, and potential research topics.

Readings include the following:

- Archaeology of Craft and Industry ("ACI"), Foreword, pp. xiii-xvii.

- Introduction: Craft, Industry, and Heritage, ACI, pp. 1-5.

- Manufacturing and Anthropogenic Impacts, ACI, pp. 5-7.

- Crutzen, P. J., and E. F. Stoermer. 2000. The "Anthropocene." Journal de Physique IV 12: 1–5 (on electronic reserve).

- Braje, T. D. 2015. Earth Systems, Human Agency, and the Anthropocene: Planet Earth in the Human Age. Journal of Archaeological Research 23: 369–396 (on electronic reserve).

Week 2. Sept. 4. Definitions, Methods, and Theories.

Readings include the following:

- Definitions, Methods, and Theories, ACI, pp. 7-21

- Excavating Histories of Craft and Industrial Enterprises, ACI, pp. 21-22

- Burke, C., and S. M. Spencer-Wood. 2018. Introduction. In Crafting in the World: Materiality in the Making, edited by C. Burke and S. M. Spencer-Wood, 1-16. New York: Springer Press (on electronic reserve).

Week 3. Sept. 11. Making and Harvesting Commodities:

Episodes of Craft Growing to Industry

Readings include the following:

- Rivers and Textiles, ACI, pp. 23-26.

- Winning and Losing in Cornell’s Pottery, ACI, pp. 23-26.

- Spinning Whimsies at Dyott’s Glassworks, ACI, pp. 27-31.

- Hand Tools, Trip Hammers, and Castaways at John Russell’s Cutlery, ACI, pp. 31-36.

- Kelly, S. E. 2013. The Role of Technological Transitions in the Development of American Ceramic Industries: Elijah Cornell and the Shift from Redware to Stoneware Production. Historical Archaeology 47(4): 45–70 (on electronic reserve).

- Starbuck, D. R. 1983. The New England Glassworks in Temple, New Hampshire. IA: Journal of the Society for Industrial Archaeology 9(1): 45–64 (on electronic reserve).

- Nassaney, M. S., and M. R. Abel. 2000. Urban Spaces, Labor Organization and Social Control: Lessons from New England's Nineteenth-century Cutlery Industry. In Lines that Divide: Historical Archeology of Race, Class, and Gender, edited by J. A. Delle, S. A. Mrozowski, and R. Paynter, 239–275. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press (on electronic reserve).

Week 4. Sept. 18. Making and Harvesting Commodities (cont'd)

Readings include the following:

- Making Do in Schroeders’ Saddle Tree Factory, ACI, pp. 36-37.

- Of Oysters, Abalone, and Salmon, ACI, pp. 37-40.

- Many Storied Domains of Bread, Biscuits, and Cheese, ACI, pp. 40-44.

- Artisan Support for an Armaments Factory, ACI, pp. 44-45.

- Bottles and Beer at Work and Home in Harpers Ferry, ACI, p. 46.

- Binderies, Tanneries, and Social Perceptions, ACI, pp. 46-49.

- Races, Lime, and Fire at Shepherdstown Cement Mill, ACI, pp. 49-51.

- Some Observations and Affordances, ACI, pp. 51-53.

- Rotman, D. L., and J. M. Staicer. 2002. Curiosities and Conundrums: Deciphering Social Relations and the Material World at the Ben Schroeder Saddletree Factory and Residence in Madison, Indiana. Historical Archaeology 36(2): 92–110 (on electronic reserve).

- Shackel, P. A., and M. Palus. 2010. Industry, Entrepreneurship, and Patronage: Lewis Wernwag and the Development of Virginius Island. Historical Archaeology 44(2): 97–112 (on electronic reserve).

Week 5. Sept. 25. Arteries and Flow

Readings include the following:

- Rivers, Canals, and Shipping, ACI, pp. 54-58.

- Building the Rail Lines, ACI, pp. 58-66.

- Dent, R. J. 1986. On the Archaeology of Early Canals: Research on the Patowmack Canal in Great Falls, Virginia. Historical Archaeology 20(1): 50–62 (on electronic reserve).

- Voss, B L. 2019. Archaeological Contributions to Research on Chinese Railroad Workers in North America. In The Chinese and the Iron Road: Building the Transcontinental Railroad, edited by G. H. Chang and S. F. Fishkin, 103–125. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press (on electronic reserve).

Week 6. Oct. 2. Arteries and Flow (cont'd)

Readings include the following:

- Iron Trajectories and Wasteful Impacts, ACI, pp. 66-69.

- Pullman’s Rail Cars and Factory Town, ACI, pp. 69-75.

- Trends and Intersections, ACI, pp. 75-76.

- Fennell, C. C. 2009. Combating Attempts of Elision: African American Accomplishments at New Philadelphia, Illinois. In Intangible Heritage Embodied, edited by D. F. Ruggles and H. Silverman, pp. 147-168. New York: Springer Press (on electronic reserve).

- Baxter, J. E. 2012. The Paradox of a Capitalist Utopia: Visionary Ideals and Lived Experience in the Pullman Community, 1880-1900. International Journal of Historical Archaeology 16(4): 651–665 (on electronic reserve).

Week 7. Oct. 9. Extraction

Readings include the following:

- Rails and Wood Cutting in West Virginia, ACI, pp. 77-78.

- Assemblies and Tools of Mining, ACI, pp. 78-83.

- From Cornwall to the Great Lakes, ACI, pp. 83-84.

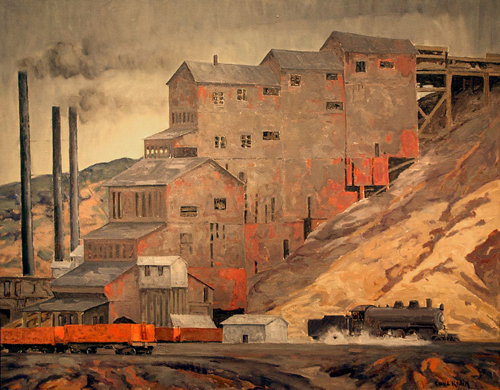

- Colossal Montana, ACI, p. 85.

- Hydraulic Assaults, ACI, pp. 85-86.

- Working the Cortez and Comstock Terrains in Nevada, ACI, pp. 86-91.

- Landon, D. B. 1999. Interpreting Social Organization at Industrial Sites: An Example from the Ohio Trap Rock Mine. Northeast Historical Archaeology 28(1): 89–103 (on electronic reserve).

- Quivik, F. L. 2022. Butte and Anaconda, Montana: Industrial Waste as Industrial Heritage. In Oxford Handbook of Industrial Archaeology, edited by E. C. Casella, M. Nevell, and H. Steyne, pp. 341-356. London: Oxford University Press (on electronic reserve).

Week 8. Oct. 16. Extraction (cont'd)

Deadline: Introductory essay due today.

Classroom presentations on subjects of introductory essay.

Readings include the following:

- Comparative Cases of Ethnicities, Cohesion, and Prejudices, ACI, pp. 91-92.

- Carving Coal in Berwind and Ludlow, Colorado, ACI, pp. 93-95.

- Mining and Murder at Lattimer, Pennsylvania, ACI, pp. 95-99.

- Ridge Barriers, Man Camps, and Magnetometers among the Oil Fields, ACI, pp. 99-101.

- Fueling Other Industries, ACI, pp. 101.

- Hardesty, D. L. 1994. Class, Gender Strategies, and Material Culture in the Mining West. In Those of Little Note: Gender, Race, and Class in Historical Archaeology, edited by E. M. Scott, 129–145. Tucson: University of Arizona Press (on electronic reserve).

- Wood, M. C. 2004. Working-class Households as Sites of Social Change. In Household Chores and Household Choices: Theorizing the Domestic Sphere in Historical Archaeology, edited by K. S. Barile and J. C. Brandon, 210–232. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press (on electronic reserve).

- Shackel, P. A. 2018. Transgenerational Impact of Structural Violence: Epigenetics and the Legacy of Anthracite Coal. International Journal of Historical Archaeology 22(4): 865–882 (on electronic reserve).

Week 9. Oct. 23. Forges, Furnaces, and Metallurgy

Readings include the following:

- Methods for the Melt, ACI, pp. 102-109.

- Early Smelting in New Mexico, ACI, pp. 109-110.

- Saugus Iron of Massachusetts, ACI, pp. 110-112.

- Trenton Steel Works of New Jersey, ACI, pp. 112-113.

- Strategies and Bloomeries in the Chesapeake, ACI, p. 113.

- Landscape Challenges in Blacklog Narrows, ACI, pp. 114-115.

- Iron Plantations in South Carolina and Maryland, ACI, pp. 115-117.

- Hunter, R. W., and I. C. Burrow. 2010. Steel Away: The Trenton Steel Works and the Struggle for American Manufacturing Independence. In Footprints of Industry: Papers from the 300th Anniversary Conference at Coalbrookdale, edited by P. Belford, M. Palmer, and R. White, 69–88. Oxford, UK: Archaeopress (on electronic reserve).

- Ferguson, T. A., and T. A. Cowan. 1997. Iron Plantations and the Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century Landscape of the Northwestern South Carolina Piedmont. In Carolina's Historical Landscapes: Archaeological Perspectives, edited by L. F. Stine, M. Zierden, L. M. Drucker, and C. Judge, 113–144. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press (on electronic reserve).

Week 10. Oct. 30. Forges, Furnaces, and Metallurgy (cont'd)

Readings include the following:

- Women of Iron, ACI, p. 117.

- Bluff Furnace of Tennessee, ACI, pp. 117-118.

- Tahawus Blast Innovations in New York, ACI, pp. 118-122.

- West Point Foundry on the Hudson, ACI, p. 122.

- Jackson Iron Company of Michigan, ACI, pp. 122-123.

- Tredegar Iron and Cannons in Virginia, ACI, pp. 123-128.

- Hawks Nest Tunnel in West Virginia, ACI, pp. 128-129.

- Innovations, Pragmatic Choices, and Personal Costs, ACI, pp. 129-130.

- Seely, B. E. 1981. Blast Furnace Technology in the Mid-nineteenth Century: A Case Study of the Adirondack Iron and Steel Company. IA: Journal of the Society for Industrial Archaeology 7(1): 27–54 (on electronic reserve).

- Raber, M. S., P. M. Malone, and R. B. Gordon. 1992. Historical and Archaeological Assessment of the Tredegar Iron Works Site, Richmond, Virginia. Report for the Valentine Museum and Ethyl Corporation, submitted by Raber Associates, Richmond, Virginia (excerpts on electronic reserve).

Week 11. Nov. 6. Craft at a Prodigious Scale: Potteries of Edgefield, South Carolina

Deadline: Seminar paper abstract with key bibliographic references due today.

Readings include the following:

- Manufacturing Stoneware in Regional and Atlantic Contexts, ACI, pp. 131-141.

- Archaeological Revelations, ACI, pp. 141-151.

- Vlach, J. M. 1990. International Encounters at the Crossroads of Clay: European, Asian, and African Influences on Edgefield Pottery. In Crossroads of Clay: The Southern Alkaline-glazed Stoneware Tradition, edited by C. W. Horne, 17–39. Columbia: McKissick Museum, University of South Carolina (on electronic reserve).

- Calfas G. W. 2017. A Dragon Kiln in the Americas: European-American Innovation and African-American Industry. Journal of African Diaspora Archaeology and Heritage 6(2): 80–99 (on electronic reserve).

Week 12. Nov. 13. Prodigious Potteries (cont'd)

Readings include the following:

- Archaeological Revelations, ACI, pp. 141-151.

- Diverse Research Initiatives, ACI, pp. 151-157.

- Hunter, R., and O. Mueller-Heubach. 2019. Visualizing the Stoneware Potteries of William Rogers of Yorktown and Abner Landrum of Pottersville. Ceramics in America 2019: 112–134 (on electronic reserve).

- Goldberg, A. F., and D. A. Goldberg. 2017. The Expanding Legacy of the Enslaved Potter-poet David Drake. Journal of African Diaspora Archaeology and Heritage 6(3): 243–261 (on electronic reserve).

Week 13. Nov. 20. Heritage Dynamics and Concluding Observations

Readings include the following:

- Evolving Questions and Methods, ACI, pp. 158-163.

- Heritage Preserved and Repurposed, ACI, pp. 163-166.

- Future Prospects, ACI, p. 167.

- Belford, P. 2014. Contemporary and Recent Archaeology in Practice. Industrial Archaeology Review 36(1): 3–14 (on electronic reserve).

- Casella, E. C. 2005. "Social Workers:" New Directions in Industrial Archaeology. In Industrial Archaeology: Future Directions, edited by E. C. Casella and J. Symonds, 3–31. New York: Springer (on electronic reserve).

- Palmer, M., and H. Orange. 2016. The Archaeology of Industry: People and Places. Post-Medieval Archaeology 50(1): 73–91 (on electronic reserve).

- Orange, H. 2015. Introduction. In Reanimating Industrial Spaces: Conducting Memory Work in Post-industrial Societies, edited by H. Orange, 13–27. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press (on electronic reserve).

Thanksgiving Break! Classes do not meet Nov. 23 to Dec. 1.

Week 14. Dec. 4. Seminar Paper Presentations and Workshop

Classroom presentations and discussion of seminar papers.

Week 15. Dec. 11. Seminar Paper Presentations and Workshop

Classroom presentations and discussion of seminar papers.

Deadline: Final seminar papers are due by 4:00pm on Dec. 20.

Last updated: Nov. 13, 2022

|