inter alia

2/9/09

Vocabulary

A few nights ago, I was talking with Sasha over dinner. I don’t even recall what we were talking about, but he asked me a kind of procedural question: “Why don’t people do that in such-and-such a way?” “Well,” I replied, “if you did things that way it would be too…” I paused, looking for the right way to explain this to a six year-old. “Labor intensive?” came his little voice, offering a suggestion. Yes, son, it would be too labor intensive.

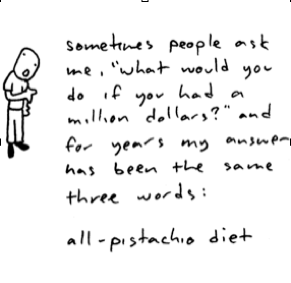

How much vocabulary is too much? I have this question on my mind a lot these days as I attempt to funnel an entire new language into my head—the words that I can just transform from English or Italian are fine (la liberté, la solution, le langage), but as to the rest: some are surprisingly easy (chaque, la fois, le même) while others pose problems from the phonetic (cependant, malhereusement) to simple ignorance (how do you say “perfino” in French? What’s the equivalent of “regardless”?). Sometimes I have this feeling:

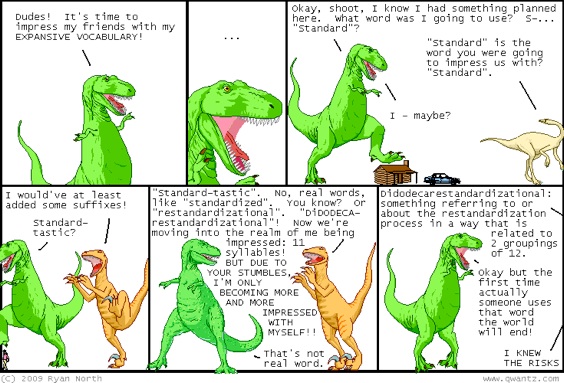

When six-year old Sasha says something is “labor intensive,” I worry a little (but only a little, as I’ll explain in a moment). All language is social, both in its meaning and its use. The word “penultimate” means second-to-last. I love the fact that we have a word that means “second-to-last” and I use it when I get the chance (which, as you might imagine, is not very often). But it has a social value as well. It is a word that indicates a certain level of education—that its social meaning, if you like. But words also place social demands on the people that are used with—or against. To say “this is your penultimate chance” is to play a social game, and a somewhat risky one: you are demanding that the other person (your interlocutor, to use another one of “those” words) recognize your words and respond to. They might sneer at you for being an egghead (most), or they might indicate that they, too, have this level of socio-linguistic mastery (a few). They might (this is the rarest reaction of all) calmly ask what “penultimate” means. I’ve only ever met one person who did that regularly, and I was impressed. It sent a different social message: I will not let you play the vocabulary game with me.

But here’s the thing. When I was young, I would trot out a nice “penultimate” from time to time. But I would also go one better—oh, you know penultimate, do you? Well, how about a nice antepenultimate chance? To say “antepenultimate” is a gesture that is clearly offensive (that is, on the offense, aggressive), a provocation, and one that carries an expectation of victory. It is that carefully prepared and researched knowledge that I talked about in an earlier post that is the real triumph of geekiness. All this reminds me of a certain dinosaur we all know:

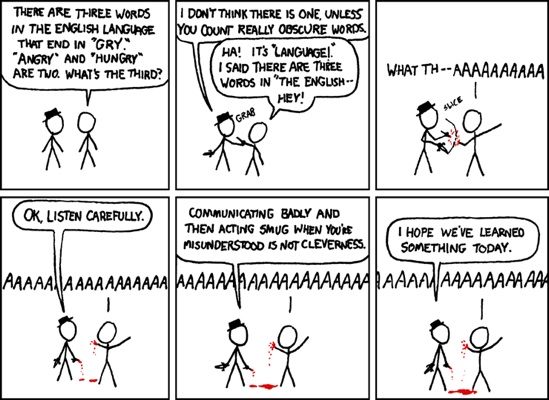

The good news is that Sasha shows no sign of enjoying his knowledge, treasuring his moments of superiority, the way that I did. Other kids called me the “walking dictionary,” and it wasn’t a compliment. Words can be dangerous:

UPDATE

This is what I get for my optimism. Another kid called Sasha a “braniac” at school today, so we had a little talk about not volunteering information around people who are not your friends. I have to be careful because he took my previous talk about how you shouldn’t show off to mean that he should pretend to not know the answers on a placement test at his school and pretend that he didn’t know how to swim at all when he went for swimming lessons.

Darwin

More on words, and Charles Darwin. Longtime readers of the blog know I’m a big fan of evolution, evolutionary psychology and in general, evolutionary explanations. Darwin is on the 10 pound bill in England, and here in Paris you might see statues of him. At all the kiosks here there’s a special issue of a magazine entirely about him. It says something like “Charles Darwin, genius of his time.” Here’s what AP uses as their headline: “A Theory Still in Controversy.”

I know, I know, it sells newspapers in America, but the fact remains that Darwin’s theory is about as controversial as the theory of gravity, or the theory that the Earth is round like a ball. Only in the US is this considered a controversy, and the controversy should be over why the media continues to pretend that there is some dispute. There are, for example, people who still believe that the Earth is flat, just as there are people who believe that aliens from outer space built the pyramids. Some people believe that they know the location of Atlantis and its fusion reactors. The newspapers do not run stories about the “continuing pyramid controversy” or “the flat earth debate,” stories in which they oh-so-impartially and oh-so-fairly report “both sides of the story.” Quote a scientist who believes in the “round earth theory,” and then quote a spokesperson from the Flat Earth Institute. Easy! And your readers are so much better informed! That’s the shameful approach taken by US News and World Reports on the subject. I believe many issues have two sides, but some have only a side and a half. After Dolly the sheep was cloned, for about a year, there was one scientist who refused to believe that actual cloning had taken place. One. So every news story about the cloned sheep featured two people: the one disbeliever, and a randomly selected, exasperated scientist who belonged to the other 99.9999999% of the scientific community.

Some stories aren’t stories because there is just one side, and one narrow, lunatic fringe. Forbes magazine agrees—which was why it decided to give all its space to a young-earth creationist, with no space for a rebuttal. Isn’t Forbes a business magazine? Like, say, pharmaceuticals? You know that you can’t do anything in medicine or biology without evolution? Like, nothing, right? So, when will the neoliberals and multinationals get together to say “we can no longer politically join forces with cretins hellbent on dragging science back to the stone age, because, uh, our livelihood kind of depends on that not happening”? The Forbes article goes as far as to repeat the slander that graced the unintentional disaster movie Expelled, which attempted to link Darwin to genocide, racism and the Nazis. I can link Greek mythology and underwear to the Nazis, too, so everyone’s going commando and tossing out the d’Aulaires books here at chez Rushing tonight. So should Darwin be on the ten dollar bill, or is he a Nazi? The American press knows the answer, don’t worry! Sometimes how you frame the debate should be the debate.

Darwin on the ten pound bill

Hitler on the ten pound bill—see the connection?

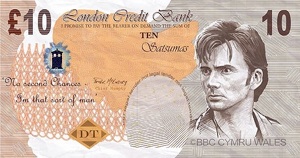

Someone with Photoshop and too much time: but in any case,

Darwin led directly to Dr. Who and the Nazis!

Plagiarism

Many of you know of my long uphill battle against student plagiarism, which reached a kind of demonic apotheosis when I had to fail half of an entire class for plagiarizing recently. Literally half. Fun times. Anyway, in addition to my many humorous stories of catching plagiarists (my favorite line so far: “for an undergraduate not majoring in literature, you seem to be astonishingly familiar with the work of scholars who ceased publishing before you born—indeed most of the journals you cite stopped being published before you were born”), I have had some bizarre plagiarism experiences from the other side. Several years ago, I was contacted out of the blue by a mysterious person on email who told me straight up that they were using an assumed name and a fake email address. This person believed, I was informed, that a syllabus that he or she had recently seen had been plagiarized from my syllabus, but would not say who any of the people involved were or where this had happened.

I am a certified internet genius™, however, and was able to figure out what university this was at (small state school, California), and narrowed it down to a group of about three people as to who was writing. The author sheepishly admitted that this was correct, but would still not give further details. The whole thing was rather bizarre, mostly because I do not regard my syllabi as my private intellectual property, so there was nothing to be stolen, and that’s more or less how I responded (for the record, the professor in question had copied portions of my syllabus). Look, some things are on the web and are not to be taken without giving due credit, like articles or books. Other things are there and meant to be taken and circulated, like syllabi and funny pictures of Hitler in a tiara or the Doctor on the ten pound note. I never claimed that I made those images (I didn’t), but I didn’t bother linking to them because it’s the internet. You probably know how to find a picture of Hitler on the ten pound note, don’t you? Type “Hitler ten pound note” into Google image search. Try it. Lots of people have probably copied my website for CWL 242, and evidently some people liked my syllabus so much they decided to use some of those great ideas for themselves. Good for them. Now, if they announced in a faculty meeting: “this is my syllabus and I wrote every word of it myself,” well that’s not so great, but who does that besides an obviously guilt-ridden individual? My syllabus has my name on it the same way my office door does—I don’t pretend to own either one, even if they have some connection to me.

So what we had was a vindictive colleague hoping to bring one of his or her fellow faculty up on charges of some kind. Okay. That sort of thing happens in our small, petty world pretty frequently. But at Southern Illinois University it’s reached whole new level. A group of faculty have decided to accuse anyone and everyone of plagiarism: the president, the faculty, the students, and finally their own plagiarism code. Get it? The irony?! They borrowed Indiana University’s plagiarism policy and didn’t cite it. This is journalism at its finest! And what about those plagiarizing hacks who stole IU’s plagiarism policy and didn’t give due credit?

Good for them. Because I don’t think I got into this business to reinvent the wheel every time I need a wheel. If Indiana University has a good plagiarism policy then everyone should copy it. Sure, it’s nice to include an acknowledgement, but it isn’t necessary—no one claimed intellectual ownership of IU’s plagiarism policy, and no one should. It’s a faceless corporate organizational document. It represents work that no one should ever have to do again and it does not represent original thought or individual research. I’m guessing no one signed their name to it, and no one should. Let us take a moment to silently thank all those who have made faculty bylaws, all those syllabi, all those CD cover templates, and all the other things that the internet was created to share effortlessly and easily.

And so I sign and counterfeit.

PS. If you like words, perhaps you’d like to read a sestina about Buffy, the Vampire Slayer. There are only a handful of really good sestinas in the McSweeny’s collection, and this may be one of them.

Words

My Six Word Answer never varies: